Study of Karelian stone־tool industry and far-flung distribution suggests hunter-fisher-gathers wanted something beyond functional tools

The sleek, gleaming, green axes and adzes made from volcanic metatuff may not dispel bad vibes, but they are attractive. This might be why there was such large demand for them in Neolithic northeastern Europe, a demand fulfilled by one industrial production complex, near the only metatuff deposit in the region.

Excavations at just one of 40 identified workshops along the Shuya River near Onega Lake in the Russian Rrepublic of Karelia yielded 350,000 lithic finds, 84 percent of which were metatuff, write Alexey Tarasov and Kerkko Nordqvist in the Journal of Antiquity. Radiocarbon dating of organic matter associated with 77 Neolithic and Eneolithic sites in Karelia indicates that this rare deposit of greenish volcanic rock was exploited starting about 6,000 to 5,000 years ago.

Operating from just two prehistoric quarries (identified to date), this Neolithic version of an Amazon Fulfillment Center was estimated to have a production scale of hundreds of thousands of tools over the lifetime of this prehistoric industry. Excavation at just one workshop produced somewhere between 500 to 1,000 finished tools.

This output must have drastically surpassed the local community’s needs, and a recent article surmises they had a sprawling distribution system to boot.

The analysis of metatuff tool distribution in Neolithic Eurasia published in Antiquity postulates that these workshops provided tools that reached fellow hunter-fisher-gatherers living as far as 1,000 kilometers away.

Tarasov, from the Russian Academy of Sciences, and Nordqvist, from the University of Helsinki, studied 1,355 preforms and 1,268 finished tools, their geographical distribution, and context. That is how they came to realize there had to have been a massive distribution network in prehistoric Karelia.

“It was quite an efficient network in that it really reached every place that people were inhabiting,” says Nordqvist. “Of course you most likely didn’t order it, but it was just kind of a thing that came.”

It bears adding that based on archaeological evidence, long-distance trade preceded not only writing but the advent of the domesticated quadruped by thousands of years.

All in all, the span of the greenstone finds stretches 1,900 kilometers, from Finland and Sweden to Kazan and Eastern Siberia.

This seems extreme considering there are no signs of agricultural development at the time in Karelia – a constraint elaborated below, and there are other materials that would make equally viable stone tools. In fact, metatuff is rather difficult to knap.

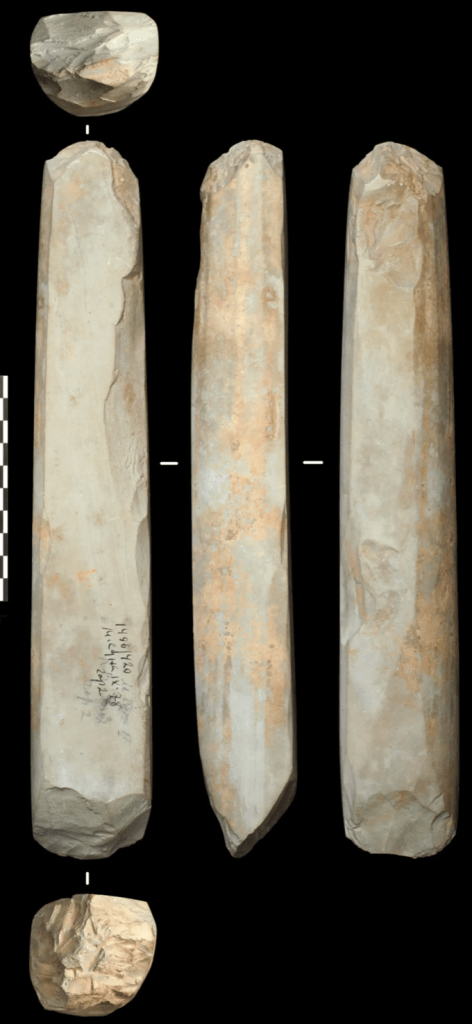

Tarasov experimented with the complex and specialized four stage process of working metatuff to produce the sort of finely crafted artifacts found across prehistoric north-eastern Europe and attests that it is not easy.

The Russian Karelian lithic industry is characterized by distinctive cross-sections and the majority of the tools are made from metatuff. Crafting the trapezoidal or triangular shaped tools is a tedious process that this community seemed to have mastered.

Given that difficulty, how did tools made of these green rocks become the object of far-reaching trade?

Green ‘crystal’ healing

Speculations about why these tools were so desirable abound even though the answer might be as simple as their appealing appearance. Perhaps Neolithic style included accessorizing with a trendy Russian Karelian fluted adze: 8,000 years ago, the people around Lake Onega were already accessorizing with elk teeth. Maybe the workshops had a killer ad campaign.

Or: Some people to this day revere pretty rocks because they believe they can heal bad juju—a medical practice with no scientific grounding—or something along those lines. Even in the Kalahari, more than 100,000 years ago, someone was hoarding crystals, and there too, we don’t know why. In fact possibly an attraction to pretty rocks predates modern humans.

Tarasov and Nordqvist dive into some of the more complex reasons that may underlie the development of this vast industry.

Some of the largest and finest Karelian specimens are found in a detached context, leading Tarasov and Nordqvist to postulate they were offerings. Perhaps animistic offerings. (Approximately 1,200 petroglyphs including images of birds, animals and human-animal hybrids at Lake Onega were just added to the UNESCO World Heritage List this past July along with other petroglyphs near the White Sea.)

But not all these artifacts are in pristine condition. Those potentially offered up to the spirit animals contrast drastically with less developed pieces exhibiting heavy wear and tear, which are commonly found in mundane contexts.

“More things became involved in what they thought was important and what they needed, and what they wanted, and most likely those reasons make no sense to us,” said Nordqvist. “They started paying attention to certain characteristics and the origin might have also been important.”

Unbalanced patterns of distribution favoring communities to the west of the workshops make the pair think these tools might also have denoted symbolic or socioeconomic relationships between the hunter-fisher-gatherer communities.

They could have served to maintain relationships—burying the green axe, if you will—or to indicate that groups to the west were wealthier in desirable commodities. Nordqvist does admit the difficulty of excavating farther into eastern Russia may be skewering their results.

There are also significantly more waterways to the west, leading the pair to assume this mainly fishing-subsisting community traveled largely via these water highways.

Metatuff was of course not the only raw material available to the Karelian people. Their artifact assemblage includes tools made of flint, points made of slate, artifacts made of hammered native copper, jewelry made of amber, and more. Flint is rare in much of northeastern Europe but was imported to Karelia, both in raw form and as finished artifacts.

The sophisticated hunter-gatherer

Information on how tool working with metatuff specifically began in Karelia is limited, but Nordqvist believes it began as much as 4,000 years before the vast Karelian industry started.

Until fairly recently it had been assumed that complex societies and industries couldn’t form until agriculture provided a relatively reliable surplus for the community. There is growing evidence that it isn’t so. Also, regarding north-eastern Europe, agriculture arrived relatively late, partly because the climate isn’t conducive to farming. The terrain, soil and climate made the development of an agrarian society difficult, and Nordqvist thinks the people continued to rely on hunting and gathering. Yet they had a sophisticated metatuff industry and distribution network.

“This is a very good example that you can find very elaborate things and very complex systems even in hunter-gatherer societies,” he says.

In this case, clearly they were devoting time to producing these greenstone artifacts, that necessarily detracted from time they could have used to provide sustenance: “So, they must have been certain they would still survive the next winter,” he says.

Perhaps the starkest evidence that hunter-gatherers were capable of complexity is being unearthed these very days in Turkey, where archaeologists are revealing that the “world’s first temple”, Gobekli Tepe, was not alone; Neolithic hunter-gatherers built at least 12 monumental sites over 11,000 years ago.

The next steps in understanding this complex greenstone industry in Karelia include further excavations at the workshops on Lake Onega and microscopic analysis of the tools.

Nordqvist thinks that understanding better what the green tools were used for will shed some light on whether or not they were used for specialized, possibly even symbolic activities. Generally most are quite heavy and big, so one theory is they were used for woodworking. But that will remain in the realm of speculation until the polished green rocks get under a microscope.

Originally published online on Haaretz in the Archeology section